- Home

- Daniel B. Schwartz

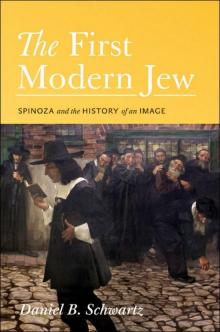

The First Modern Jew

The First Modern Jew Read online

The First Modern Jew

The First Modern Jew

Spinoza and the History of an Image

Daniel B. Schwartz

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-14291-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011942572

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been published with the generous assistance of the

Foundation for Jewish Culture and its Sidney and Hadassah Musher

Subvention Grant for First Book in Jewish Studies

Excerpt from “The Spinoza of Market Street” from THE COLLECTED STORIES by

Isaac Bashevis Singer. Copyright © 1982 by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Reprinted by permission

of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpts from THE FAMILY MOSKAT by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Copyright © 1971 by

Isaac Bashevis Singer. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpt from “The New Winds” from IN MY FATHER’S COURT by Isaac Bashevis

Singer. Copyright © 1966 by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Copyright renewed 1994 by Alma

Singer. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Excerpts from LOVE AND EXILE by Isaac Bashevis Singer. Copyright © 1984 by Isaac

Bashevis Singer. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

This book has been composed in Janson Text

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Alisa

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface and Acknowledgments

Note on Translations and Romanization

INTRODUCTION

Spinoza’s Jewish Modernities

CHAPTER 1: Ex-Jew, Eternal Jew:

Early Representations of the Jewish Spinoza

CHAPTER 2: Refining Spinoza:

Moses Mendelssohn’s Response to the Amsterdam Heretic

CHAPTER 3: The First Modern Jew:

Berthold Auerbach’s Spinoza and the Beginnings of an Image

CHAPTER 4: A Rebel against the Past, A Revealer of Secrets:

Salomon Rubin and the East European Maskilic Spinoza

CHAPTER 5: From the Heights of Mount Scopus:

Yosef Klausner and the Zionist Rehabilitation of Spinoza

CHAPTER 6: Farewell, Spinoza:

I. B. Singer and the Tragicomedy of the Jewish Spinozist

EPILOGUE:

Spinoza Redivivus in the Twenty-First Century

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Illustrations

FIGURE 1.1. Anonymous, Portrait of Spinoza, ca. 1665.

FIGURE. 2.1. Johann Christoph Frisch, Portrait of Moses Mendelssohn, 1786.

FIGURE. 3.1. Julius Hubner, Portrait of Berthold Auerbach, 1846.

FIGURE. 4.1. Title page, S. Rubin’s Hebrew translation of Spinoza’s Ethics (Vienna, 1885).

FIGURE. 4.2. Samuel Hirszenberg, Uriel Acosta and Spinoza, 1888. Photo from postcard.

FIGURE. 4.3. Samuel Hirszenberg, Spinoza, 1907.

FIGURE. 5.1. Photograph of Yosef Klausner, 1911.

FIGURE. 5.2. David Ben-Gurion’s diary for August 7, 1951, containing, in the prime minister’s handwriting, his transcription, in the original Latin, of the passage from chapter 3 of Spinoza’s Theological-Political Treatise that begins “were it not that the principles of their religion discourage manliness . . .”

FIGURE. 5.3. Letter from the chief rabbi of Israel, Isaac Halevi Herzog to G. Herz-Shikmoni, 6 Tishre 5714 (September 15, 1953), suggesting that the rabbinic ban on Spinoza’s writings no longer applies.

FIGURE. 6.1. Photo of I. B. Singer as a young man.

Preface and Acknowledgments

On a blustery October morning five years ago, I went to the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in lower Manhattan to speak at a most unusual semiseptcentennial. Headlining the YIVO schedule for that day was an event entitled: “From Heretic to Hero: A Symposium on the Impact of Baruch Spinoza on the 350th Anniversary of His Excommunication, 1656–2006.” The list of speakers read like a “who’s who” of recent Spinoza scholarship, with names like Steven Nadler, author of Spinoza: A Life, the definitive biography of Spinoza in English; Steven B. Smith, a leading authority on Spinoza’s political thought; and above all Jonathan I. Israel, author of two magisterial works on Spinoza and the European Enlightenment. Household names for me, but not, I figured, for those outside the academy, even for the stereotypical New York Jewish culture-bearers. I did not know what size audience to expect, but an auditorium that seated 250 filled to three-quarter capacity seemed optimistic.

I guessed wrong. By the time I arrived the event had already sold out. This came as a surprise not only to me. One journalist, blogging about the conference in the New York Observer, wrote: “I almost didn’t get in. The conference was sold out, there were scores of people waiting for an extra ticket on 16th St. I of course played the press card, but happily for all of us, Yivo lowered the screen in its main hall, allowing the overflow to watch the event on simulcast.”1 Whether they sat in the auditorium or the hall just outside, well over three hundred New Yorkers chose to spend their Sunday afternoon listening to six hours of lectures on a seventeenth-century philosopher whom few in the audience, frankly, were likely to have read.

The spillover crowd for this YIVO symposium in 2006 was simply one example of a surge of interest in Spinoza since the turn of the millennium that transcends the academy and cuts across nations, disciplines, and genres. We find evidence of this fascination in the audience for Israel’s Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity (2001), which has been called “one of the most important books on Spinoza in the past hundred years” and—notwithstanding its forbidding length—“certainly among the most popular.”2 We find it in the fact that a weekly news magazine like Le Point—a kind of French equivalent to Time and Newsweek—would choose to run a cover story on Spinoza in the summer of 2007, labeling the Amsterdam heretic “the man who revolutionized philosophy.”3 And we find it in the enthusiastic response to David Ives’s 2008 play New Jerusalem: The Interrogation of Baruch Spinoza, whose “box-office success” was referred to by one of the most recent repertory theaters to perform it as “one of the more staggering surprises of the summer.”4

I, too, am fascinated by Spinoza. But I am also fascinated by the fascination with him, by the extremity of feeling this early modern philosopher, dead more than three hundred years, continues to evoke. Moreover, the Jewish fascination—because it reverberates through practically every major Jewish ideological response to modernity and is so closely bound up with the struggle to define what it means to be a modern, “secular” Jew—has a fascination all its own, and it is the subject of this book.

In the pages that follow, we will come across several testimonies by modern Jewish writers that recount their initial discovery of Spinoza as a transcendent, even revelatory experience. My road to Spinoza, I confess, began with much less fanfare, while I was a graduate student in Jewish history at Columbia University. Asked by one of my advisors, Yosef H. Yerushalmi, about my plans for a dissertation topic, I spoke vaguely about my interest in histori

cal consciousness and modern Jewish identity; he recommended a study of the Jewish reception of Spinoza. From his crowded bookshelves he pulled down what would prove my first and most essential reference work: Adolph Oko’s Spinoza Bibliography, with its over six hundred pages of entries of “Spinozana.” Steering me to this subject, while at the same time withdrawing to enable me to write this work as I saw fit, would be reason enough for thanks. I am also grateful to Professor Yerushalmi for his meticulous comments on early drafts of individual chapters, for his rich and stimulating pedagogy in Jewish history, and for the confidence he expressed in my work and me at key moments over the years. I am deeply saddened that he died before this book was complete, though also appreciative that I was fortunate enough to be one of the last of a long line of trained scholars in Jewish history to benefit from his vast erudition and thoughtful tutelage. May his memory be for a blessing.

I am equally indebted to Michael Stanislawski, a master teacher of modern Jewish intellectual and cultural history and my other mentor throughout graduate school. There are only so many “highlights” in graduate school, yet certainly our independent study of one of his many areas of expertise, the East European Haskalah, where I first encountered various thinkers who figure prominently in this book, ranks among them. Moreover, the deftness with which he weaves together literary and historical analysis in his writing has served as a model and inspiration for my own work. Finally, I am thankful to Professor Stanislawski for his expert direction of this project in its dissertation stage, for reading drafts so rapidly and incisively, and for providing repeated encouragement along the way.

Many other teachers, colleagues, and friends have played an important role in the evolution of this book from conception to completion; here I can single out only a few for mention. Sam Moyn contributed greatly to this study as an early backer and penetrating critic; I especially appreciated his apt remarks on my treatment of the German Jewish reception of Spinoza. Similarly, Jeremy Dauber gave charitably of his time to discuss initial drafts on Spinoza’s East European Jewish reappropriation. Steven Nadler brought his unsurpassed knowledge of Spinoza’s biography to bear on my early chapters; I thank him as well. Others engaged in the study of Spinoza’s reception at some level—including Allan Nadler, Jonathan Skolnik, and Adam Sutcliffe—generously welcomed me into the club, inviting me to speak at conferences, acting as respondents for my papers, and just simply giving me the benefit of their conversation. I thank Adam Shear for his astute comments on individual conference papers as well as on my original dissertation. David Biale’s work on historical heretics and modern Jewish identity was an early inspiration for this study, and I am grateful to have benefited from his close reading of my work as it has evolved from dissertation to book. Jim Loeffler, Noam Pianko, Deena Aranoff, and Rebecca Kobrin were invaluable as readers, interlocutors, and friends at different points in this process. Alan Stadtmauer served, yet again, as a pivotal sounding board in the gestation of my ideas. And Lauren Wein, with her keen editor’s eye and insider’s knowledge of the world of publishing, offered crucial counsel at many anxious moments.

Since arriving at George Washington University, I have learned enormously from my colleagues in the history department and Judaic studies program. I am especially grateful to Max Ticktin, who read Yiddish poetry on Spinoza with me one semester every Friday morning and made thoughtful comments on an early draft of my chapter on I. B. Singer; to Andrew Zimmerman, who was kind enough to read my book manuscript when it was close to finished and to help me see how its argument appeared to a general reader; and to Tyler Anbinder, Robert Eisen, Jenna Weissman Joselit, Bill Becker, Marcy Norton, Chris Klemek, and Yaron Peleg for their mentoring and advice. It was also serendipitous that I joined the George Washington faculty at around the time Brad Sabin Hill became the head librarian of the Kiev Judaica collection. I have profited greatly from his knowledge of Hebrew and Yiddish Spinozana, not to mention from his friendship.

In the fall of 2009 I was fortunate to participate in a research group on the topic of “Secularism and Its Discontents: Rethinking an Organizing Principle of Modern Jewish Life” at the Center for Advanced Jewish Studies (CAJS) at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The months spent as the Louis and Bessie Stein fellow in residence at the CAJS and on leave from teaching were a boon to this project. They allowed me the time to write an additional chapter, for one, but, even more important, were the Wednesday-afternoon presentations, and the spirited question-and-answer sessions that followed, which helped immensely to sharpen and deepen my framing of the key questions in the book. Special thanks to David Ruderman, for offering me the fellowship, and to David Myers and Andrea Schatz, for not only conceptualizing the topic of our research group, but for their probing questions and helpful comments on my own work.

Beyond CAJS, I would like to acknowledge the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, the Center for Jewish History, and the Lane Cooper Fellowship for their financial support while this work was in its dissertation stage; the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences at George Washington University and the Gudelsky Foundation for similar support during the process of revising the dissertation into a book; and the Foundation of Jewish Culture for their support in both phases, first in the form of a dissertation fellowship and, toward the end, through a generous subvention grant. Thanks also go to the directors and staff of the archives and libraries I consulted, which are listed in the bibliography.

Princeton University Press has published many important books by or on Spinoza over the years, and so I am extremely gratified that my book will appear under their imprint. My editor Fred Appel has been a strong advocate of this project from the beginning. I thank him for soliciting a book proposal from me before the manuscript was yet complete, and for his patience and encouragement ever since. Many thanks as well to his assistant Diana Goovaerts for her help in keeping the project moving along, to Brigitte Pelner for steering the book through the production process, and to Marsha Kunin for her scrupulous and thoughtful copyediting.

David Singer, a terrific scholar of Jewish intellectual history who also happens to be my father-in-law, has been a wonderful guide throughout this process. His role has spanned from preliminary sleuthing, to reading everything from my first stab at a draft of a dissertation chapter, to the final draft of this book’s epilogue. As for my mother-in-law, Judy, her matchless combination of calm, empathy, and intelligence makes her one of the best people I know to talk to. Both have my deepest admiration. To my parents, Steven and Helen, who have remained unstinting in their belief in me and the path I have chosen through its peaks and valleys, and who have blessed me in ways too numerous to mention, I am exceedingly grateful. My siblings as well as sisters- and brothers-in-law have likewise been a considerable source of support.

Finally, I want to thank my wife Alisa, to whom my debt is inestimable. This book has been long in the making. It was conceived when we were still practically newlyweds, and the course of its development has been interrupted by times of both delirious joy and devastating sorrow. Throughout, she has made sacrifices to enable me to follow my chosen career and finish this book; throughout, she has remained a pillar of love, strength, and support—the best of wives, the best of mothers, and the best of friends. From the bottom of my heart, this book is dedicated to her. As for our two darling children, Max and Sophie, their arrival may have delayed the completion of this work somewhat, but they have made life itself immeasurably sweeter.

D.B.S.

Note on Translations and Romanization

All quotations from Spinoza’s Ethics and Letters 1–29 are taken from The Collected Works of Spinoza, trans. Edward Curley, vol. 1 (Princeton, 1985), which is almost universally regarded as the standard-bearer among English translations. Since the second volume of Curley’s edition of Spinoza has yet to appear, for citations from the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus and from the rest of the letters, I have relied on Samuel Shirley’s translation, which is included in his recen

tly published Complete Works, ed. Michael L. Morgan (Indianapolis, 2002).

For the romanization of Hebrew and Yiddish in the text, I have generally followed the Library of Congress standards, with the exception of certain personal or place names where a particular spelling has become widely accepted (e.g. Baruch instead of Barukh Spinoza, Aaron Zeitlin instead of Arn Tsaytln).

The First Modern Jew

Introduction

Spinoza’s Jewish Modernities

I.

Ask a Jew a question, the old joke goes, and he will answer you with another question. However trite, this saying seems particularly apt to the problem of defining Jewishness in the modern world, which has come to be identified with a question as terse as it is dizzyingly complex: “Who is a Jew?” While boundary questions have accompanied Jews throughout their millennial history of exile and dispersion, modernity has seen a dramatic increase in both their number and intensity. In premodern times, the near universal authority of Jewish sacred law (or Halakhah), combined with the near universal pattern of Jewish self-government, made for near universal consensus on the religious, ethnic, and corporate determinants of Jewish identity. Being Jewish meant that one was either matrilineally a Jew by birth or a convert to Judaism in accordance with Halakhah; it also meant that one belonged to the autonomous Jewish community, membership in which was compulsory for all Jews. The challenge to traditional rabbinic norms that began with the Enlightenment’s critique of religion eroded the halakhic parameters of Jewishness; the leveling of the ghetto walls as a result of Emancipation did the same for the physical barriers; and, for all the new boundaries that have been erected in the past three hundred years (in the case of the State of Israel, actual political and territorial boundaries), the situation that prevails today is one of definitional anarchy, where not only who or what is Jewish, but to an even greater extent the criteria for exemplary Jewishness, are bitterly contested. The crack in what was once more or less united in Jewish life—religion and ethnicity—has resulted in infinite permutations of Jewish identity where one or the other is primary, and at the extremes, to the prospect (if rarely the plausibility) of Judaism without Jewishness and Jewishness without Judaism. All the above have conspired to make “Who is a Jew?” a conundrum for which, indeed, there is no simple answer. We might even say that the hallmark of modern Jewish identity is its resistance to—and, at the same time, obsession with—definition. It is shadowed by a question mark that constantly looms.

The First Modern Jew

The First Modern Jew